Spinal Stenosis and Neurogenic Claudication: How to Recognize Symptoms and Choose the Right Treatment

When you start to feel a heavy, cramping pain in your legs after walking just a few blocks-then it disappears the moment you sit down or lean forward-you’re not imagining it. This isn’t just tired muscles. It’s neurogenic claudication, the most common symptom of lumbar spinal stenosis. And if you’re over 50, it’s more common than you think. About 200,000 American adults experience it every year, and the numbers are rising as the population ages. The good news? You don’t have to live with it. The better news? There’s a clear path to relief-if you know what to look for.

What Exactly Is Neurogenic Claudication?

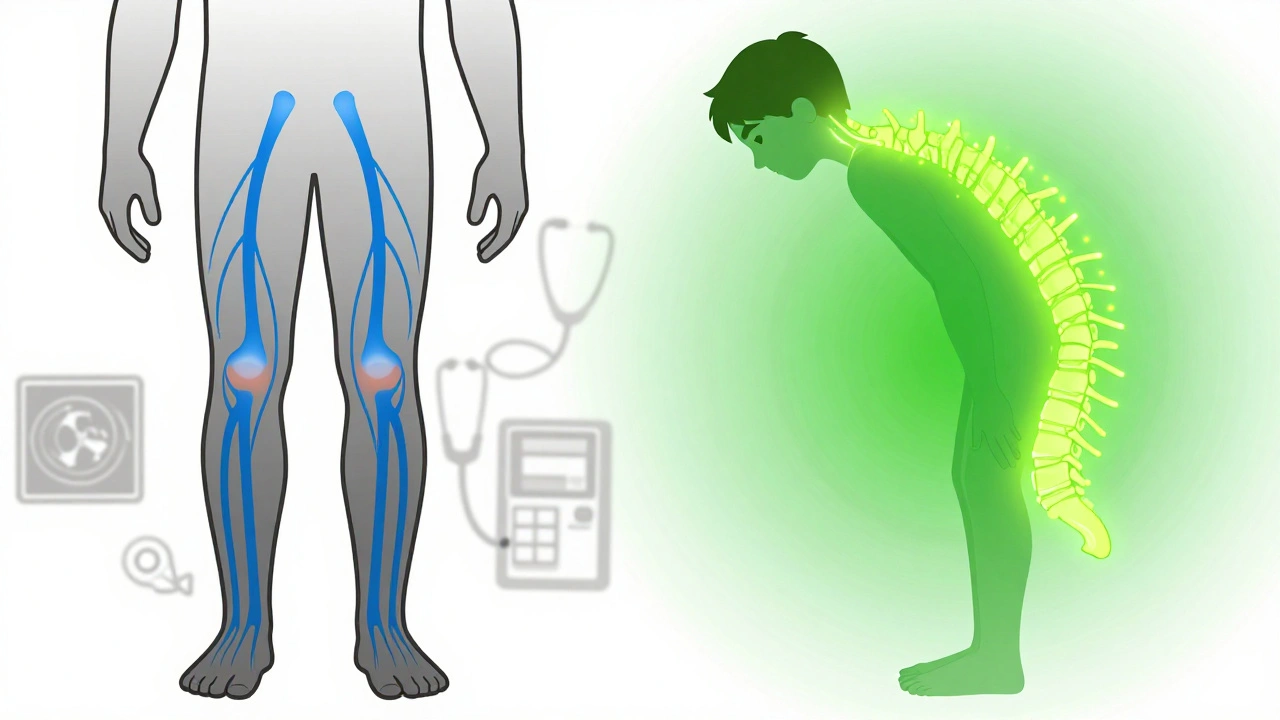

Neurogenic claudication isn’t a disease. It’s a signal. It’s your body telling you that the space around your spinal nerves in the lower back has narrowed, pressing on them when you stand or walk. This compression cuts off blood flow and irritates the nerves, causing pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness that runs down one or both legs. It usually starts slowly. At first, you might just feel a little heaviness. Then, over months or years, it gets worse. You walk less. You stop more. You start leaning on shopping carts, walkers, or kitchen counters just to keep going. The key? It’s not the walking that hurts-it’s the position. Unlike vascular claudication (which comes from poor circulation and improves with rest, no matter how you sit), neurogenic claudication only gets better when you bend forward. That’s why people with this condition often describe the "shopping cart sign"-they can’t walk far, but push a cart and suddenly they’re fine. Or they’ll sit on a bench, then stand up and walk again. It’s not laziness. It’s survival.How Doctors Tell It Apart From Vascular Claudication

Misdiagnosis is common-and dangerous. If you’re told you have "poor circulation" and given blood thinners or vascular tests, you’re not getting the right help. The difference is simple but critical:- Neurogenic claudication: Pain comes with standing or walking, eases with sitting or bending forward. Pulses in your feet are normal. You might have numbness or weakness in your legs, but no coldness or skin changes.

- Vascular claudication: Pain comes with walking, eases with rest-no matter your posture. Your feet might feel cold, look pale, or have weak or absent pulses. You may have a history of smoking, diabetes, or high cholesterol.

Why Imaging Alone Can Mislead You

You might think an MRI will give you the answer. It won’t. Not alone. Up to 67% of people over 60 have signs of spinal stenosis on an MRI-even if they have zero pain. That’s right. Their spine looks narrowed on the scan, but they walk fine. Meanwhile, some people with severe symptoms have only mild narrowing on imaging. That’s why diagnosis isn’t about the scan. It’s about the story. Your symptoms. Your posture. Your history. The MRI is just the final piece. It confirms what your body already told you. If you have leg pain that gets worse when standing, improves when you bend over, and your pulses are normal-then yes, spinal stenosis is likely. The scan just shows you where the narrowing is.

First Steps: Conservative Treatment That Actually Works

Most people don’t need surgery. In fact, 82% of those with early-stage neurogenic claudication see real improvement with conservative care. The goal? Reduce pressure on the nerves, strengthen supporting muscles, and teach your body how to move differently.- Exercise: Focus on flexion-based movements. Walking uphill, riding a stationary bike with a forward-leaning posture, or doing pelvic tilts can help. Avoid extension exercises like backbends or standing toe touches-they make symptoms worse.

- Physical therapy: A good therapist will teach you how to use your core to protect your spine, how to sit and stand without compressing your nerves, and how to use forward bending as a tool-not just a last resort. Most patients need 6 to 8 weeks of consistent therapy to see results.

- Pain management: Over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen can help with inflammation. In some cases, doctors prescribe muscle relaxants or low-dose nerve pain meds like gabapentin. But these are temporary fixes, not solutions.

When Conservative Care Isn’t Enough

If after 3 to 6 months of exercise, therapy, and lifestyle changes your pain is still keeping you off your feet, it’s time to consider more targeted options.- Epidural steroid injections: These deliver anti-inflammatory medicine right around the compressed nerves. About 50% to 70% of patients get relief for weeks or months. It’s not permanent, but it can buy you time to get stronger or delay surgery.

- Minimally invasive surgery: Options like laminotomy or interspinous process decompression (like the FDA-approved Superion device) create more space without cutting major muscles or bones. These procedures often take under an hour, require a short hospital stay, and have high satisfaction rates-78% of patients report improved function two years later.

- Traditional laminectomy: For more severe cases with multiple levels of narrowing, removing part of the bone and ligament may be needed. Recovery takes longer, but 70% to 80% of well-selected patients see lasting improvement.

What Patients Say About Their Journey

On patient forums, the same stories keep coming up:- "I thought it was my heart. Then I found out it was my spine. I was so angry I waited so long."

- "I used to walk my dog for 20 minutes. Now I walk 45, and I don’t need to stop."

- "My doctor asked if I leaned on the cart. I said yes. He said, ‘That’s it.’ Finally, someone got it."

What’s New in 2025?

The field is moving fast. In 2023, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons updated its guidelines to make structured exercise the first recommendation-not a last resort. And in early 2024, the International Spine Study Group released a new diagnostic algorithm to help doctors match symptoms with imaging more accurately. It’s not perfect yet, but it’s a step toward fewer misdiagnoses. Minimally invasive procedures are also becoming more common. Between 2018 and 2022, their use jumped by 35%. That’s because patients want faster recovery and less downtime. And with the global population over 65 expected to double by 2050, the demand for smart, effective care will only grow.What You Can Do Today

If you’re experiencing leg pain when walking:- Track your symptoms. Note when it starts, how long it lasts, and what makes it better or worse.

- Try leaning forward while walking. Do you feel relief? Write it down.

- Check your foot pulses. Press your fingers on the top of your foot and behind your ankle. Are they strong and equal on both sides?

- See a doctor who specializes in spine or movement disorders-not just a general practitioner.

- Ask: "Could this be neurogenic claudication? What tests will you do to rule out vascular issues?"

Is neurogenic claudication the same as sciatica?

No. Sciatica is pain that shoots down one leg due to a pinched nerve root, often from a herniated disc. It’s usually sharp and sudden. Neurogenic claudication is a broader, more diffuse pain, numbness, or heaviness in both legs that builds slowly with walking or standing and improves with forward bending. Sciatica doesn’t typically respond to leaning forward like claudication does.

Can I still walk if I have neurogenic claudication?

Yes-but you need to adapt. Many patients walk shorter distances, but use forward-leaning positions (like pushing a cart or using a walker) to extend their range. Regular walking in a flexed posture, such as on a stationary bike or uphill, can actually improve endurance over time. Avoid long periods of standing or walking upright without breaks.

How long does it take to see improvement with physical therapy?

Most patients start noticing changes after 4 to 6 weeks of consistent therapy, but full benefits often take 8 to 12 weeks. The key is daily practice-especially exercises that strengthen the core and teach you how to maintain a slightly forward-leaning posture during daily activities.

Are epidural injections a permanent solution?

No. Epidural steroid injections reduce inflammation around the nerves and can provide relief for weeks to months, but they don’t fix the underlying narrowing. They’re best used as a bridge-to reduce pain enough so you can engage in physical therapy or delay surgery. Repeat injections are possible, but most doctors limit them to 2 or 3 per year.

What happens if I ignore the symptoms?

Ignoring symptoms won’t make them go away. Over time, persistent nerve compression can lead to permanent numbness, muscle weakness, or even loss of balance. While pain can be managed, nerve damage is harder to reverse. Early intervention-especially with physical therapy-can prevent progression and preserve function.

Is surgery risky for older adults?

Surgery is generally safe for healthy older adults, especially minimally invasive options. Studies show patients in their 70s and 80s benefit just as much as younger patients when they’re properly selected. Risks include infection, nerve injury, or failed relief-but these are rare. The bigger risk is staying inactive. Loss of mobility leads to muscle loss, falls, and other health problems. For many, surgery restores independence.

Ryan Brady

This is why America's healthcare is broken. I've seen 3 docs in 2 years and no one asked about the shopping cart thing. Now I gotta pay for a specialist? 🤦♂️

Lisa Whitesel

If you're over 50 and still walking upright like a robot you deserve the pain. Stop being lazy and learn to bend. The solution is literally in the title of this post

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

The clinical delineation between neurogenic and vascular claudication remains profoundly underappreciated in primary care settings. A structured diagnostic algorithm, as referenced in the 2024 International Spine Study Group publication, ought to be mandatory training for all physicians managing geriatric musculoskeletal presentations.

Taya Rtichsheva

so like... you just lean forward and boom no more pain? why didnt anyone tell me this before? i thought i was just getting old lol

Mona Schmidt

This is exactly the kind of clear, patient-centered information that's missing from most medical content. The emphasis on symptom patterns over imaging is spot on. Too many people get misdiagnosed because doctors rely on scans instead of listening. Thank you for sharing this.

Guylaine Lapointe

I'm so tired of people calling this 'just aging'. It's not. It's a treatable neurological condition. And if you're still telling patients to 'just walk it off' you're doing harm. This post is a godsend for anyone who's been gaslit by their doctor for years.

Sarah Gray

82% improve with conservative care? That's a lie. My cousin had this and spent 18 months doing yoga and 'core strengthening'. Ended up in a wheelchair. The real answer is surgery. Stop pushing placebo treatments.

Kathy Haverly

They're lying about the MRI stats. 67% of people over 60 have stenosis on MRI? That's because the radiologists are paid to find something. The real problem is the pharmaceutical-industrial complex pushing drugs and injections instead of fixing the root cause. They don't want you to heal. They want you to keep paying.

Andrea Petrov

Did you know the FDA approved the Superion device after a 3-month trial with 12 patients? The same people who pushed the opioid crisis are now pushing spinal implants. Your 'minimally invasive surgery' is just another way to profit off elderly pain. I've seen the contracts.

Suzanne Johnston

There's something deeply human in the way this condition reveals itself - not through scans, but through posture, through the quiet act of leaning on a cart. It's not just a medical phenomenon. It's a silent negotiation between body and environment. We've forgotten how to listen to our bodies because we've outsourced understanding to machines.

George Taylor

I don't know why anyone would trust this article... It's got too many exclamation points, too many percentages, too many words... I mean, really? '5R-STS'? That's not a real thing. And why are they using bullet points? This feels like a pharmaceutical ad disguised as medical advice...

ian septian

Lean forward. Walk uphill. Bike seated. Stop standing straight. Do this for 6 weeks. If no change, see a spine specialist. Done.

Chris Marel

This reminds me of my uncle in Lagos. He'd lean on his walking stick and say 'the spine knows when to rest'. He never saw a doctor, but he lived to 89. Sometimes the body teaches us better than any scan.

precious amzy

The entire premise is ontologically flawed. You cannot reduce a complex neuro-mechanical phenomenon to a binary of 'bend or not bend'. This is Cartesian reductionism disguised as medical wisdom. The body is not a hydraulic system to be 'decompressed'. It is a phenomenological field of lived experience - and your algorithmic diagnostic framework is a colonial imposition on embodied truth.