Physical Dependence vs Addiction: Clarifying Opioid Use Disorder

Opioid Dependence vs Addiction Quiz

This tool helps you understand the key differences between physical dependence and addiction to opioids. Based on medical guidelines from the CDC and DSM-5 criteria, answer the following questions to see if you might be experiencing dependence or opioid use disorder (OUD).

Important: This quiz is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment.

1. How long have you been taking opioids daily for pain management?

2. Do you experience withdrawal symptoms when you skip a dose?

3. Do you continue using opioids despite negative consequences to your life?

4. Do you find yourself needing higher doses to get the same pain relief?

5. Do you experience strong cravings to use opioids outside of medical need?

When someone takes opioids for pain, they might start to feel sick if they skip a dose. Nausea. Sweating. Anxiety. Insomnia. Many assume this means they’re addicted. But that’s not true. In fact, most people who take opioids long-term develop physical dependence - not addiction. And confusing the two can cost people their pain relief, their dignity, and even their lives.

What Physical Dependence Really Means

Physical dependence is a normal, predictable response to taking opioids for more than a few weeks. It’s not a disease. It’s biology. When opioids bind to receptors in your brain, your body adapts. It starts making more norepinephrine. It changes how your nerves fire. Your system gets used to having the drug there. When you stop, your body overreacts. That’s withdrawal.

Studies show nearly 100% of patients taking opioids daily for over 30 days develop physical dependence. That’s not rare. That’s expected. The symptoms are well-documented: nausea (92% of cases), vomiting (85%), sweating (78%), anxiety (89%), yawning (76%), and diarrhea (68%). These aren’t signs of moral failure. They’re signs your nervous system is adjusting. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) measures this. A score above 12 means moderate withdrawal - and it’s treatable.

Dependence usually shows up within 7 to 10 days of daily use at doses over 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME). Tolerance often comes with it - you need more to get the same pain relief. But tolerance alone doesn’t mean addiction. It just means your body’s adapting.

What Addiction Actually Is

Addiction - now called Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) - is different. It’s not about physical symptoms. It’s about behavior. It’s when someone keeps using opioids even though it’s destroying their life. They lose jobs. Lie to loved ones. Steal money. Keep using despite overdoses, health problems, or legal trouble.

The brain changes here are deeper. Addiction hijacks the reward system. The nucleus accumbens, the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala - these areas get rewired. Dopamine pathways get stuck in overdrive. The person doesn’t use opioids because they feel good. They use them because they can’t stop. Cravings become overwhelming. A 2017 study found that 83% of people with severe OUD reported intense cravings. 89% kept using even after causing harm.

According to the DSM-5, you need at least 2 of 11 symptoms in 12 months to be diagnosed with OUD. Those include: taking more than intended, failing to cut down, spending too much time getting or using the drug, neglecting responsibilities, giving up hobbies, and continuing use despite physical or psychological problems. Only about 8% of people on long-term opioids develop OUD. That’s not a majority. It’s a minority.

The Real Danger: Mixing Them Up

Here’s where things go wrong. Doctors, patients, even family members often think withdrawal = addiction. That’s dangerous. A 2020 study found 68% of chronic pain patients believed withdrawal symptoms meant they were addicted. So they quit cold turkey - or refused to refill prescriptions. Some stopped pain meds entirely. Others switched to illicit opioids because they couldn’t get help.

One patient on Reddit wrote: “I tapered off 60 MME/day oxycodone over 8 weeks. Had withdrawal for 10 days. Never felt the urge to use recreationally. But my doctor acted like I was a junkie.”

Meanwhile, someone with true OUD might say: “I stole money from my mom. Drove two hours to get more pills. Lost my job. But I still couldn’t stop.”

The difference? One person suffered physically - and stopped. The other kept going - even when it broke everything.

How Doctors Tell the Difference

Clinicians use tools to spot the real problem. The Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) screens for behavioral risk factors - past substance use, mental health conditions, family history. About 24% of patients are flagged as high-risk. That doesn’t mean they’ll get addicted. It means they need closer monitoring.

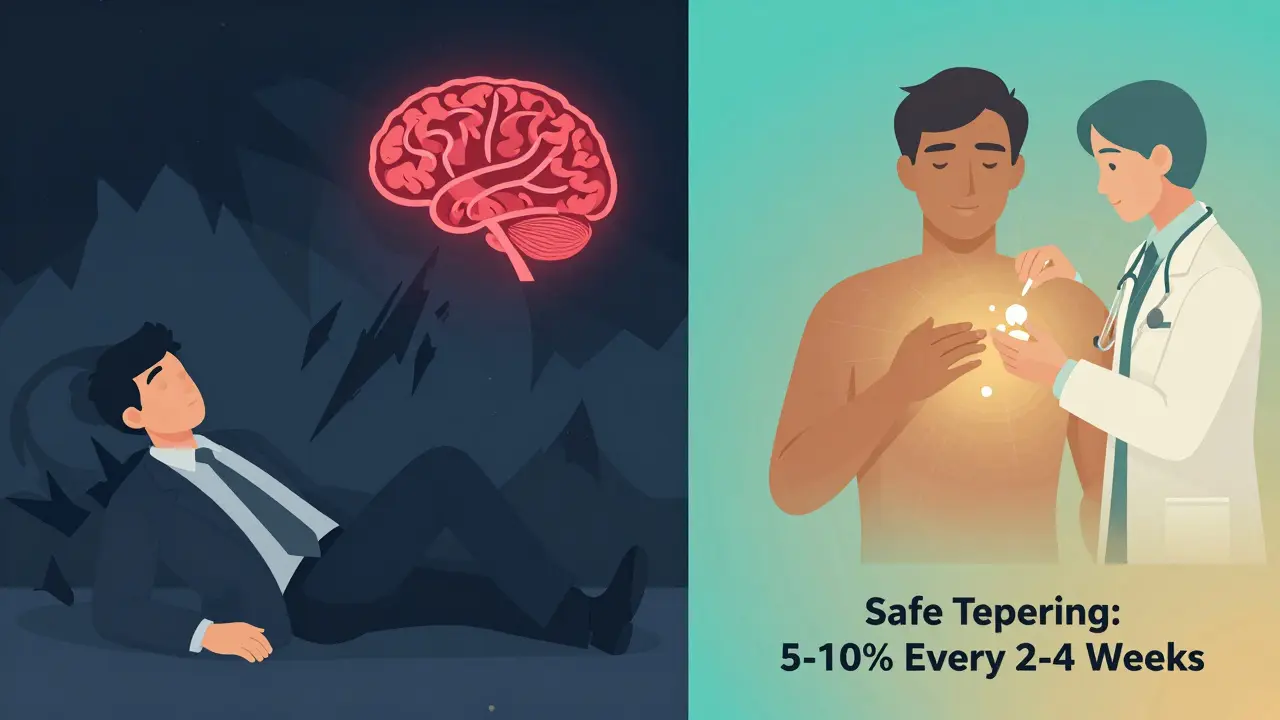

For physical dependence, the goal is safe tapering. The CDC recommends reducing doses by 5-10% every 2-4 weeks. For people on over 100 MME/day, go slower - 5% per month. Withdrawal symptoms are managed with medications like clonidine or the newer lofexidine (FDA-approved in 2023). No judgment. No stigma. Just medicine.

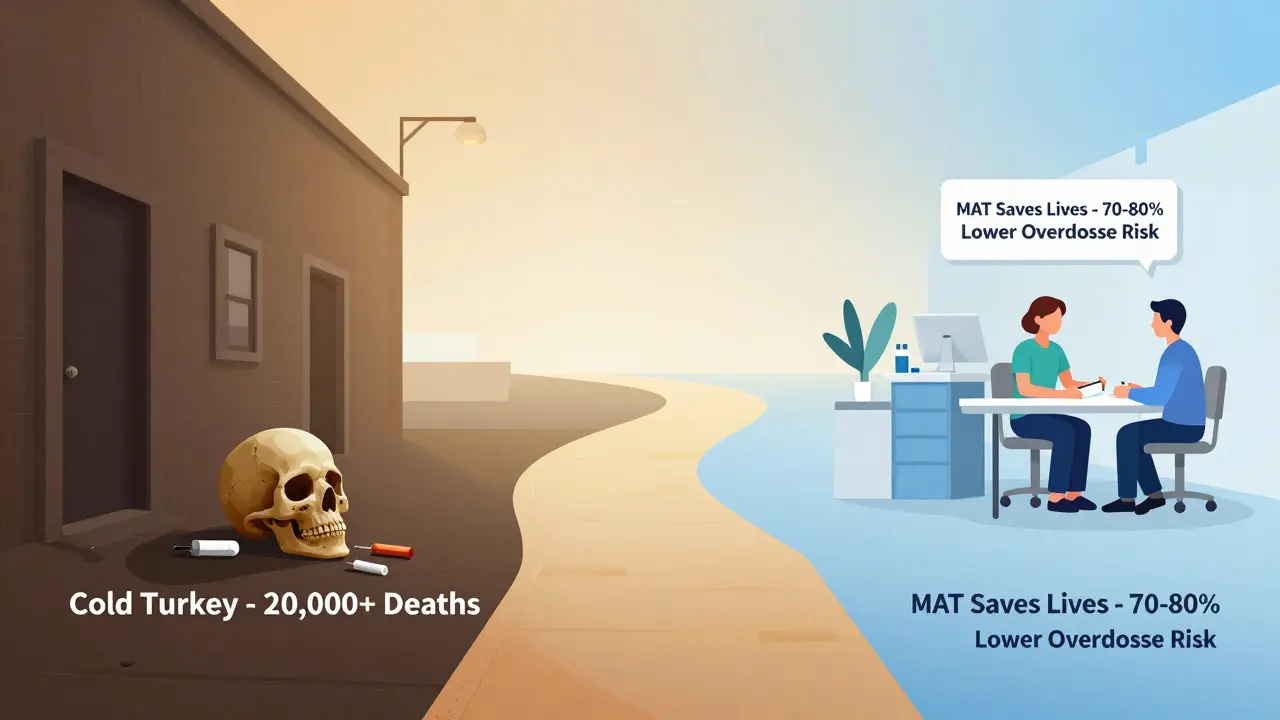

For OUD, you need Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT). Buprenorphine cuts overdose deaths by 70-80%. Methadone cuts them by 50%. These aren’t replacements. They’re treatments. Combined with counseling, they help people rebuild their lives. The American Medical Association passed a resolution in 2021 specifically telling doctors: “Don’t stop needed opioids just because a patient is physically dependent.”

Why This Matters Right Now

The opioid crisis didn’t start because people got addicted to pain pills. It started because doctors stopped prescribing them - and people turned to heroin and fentanyl. When the CDC released its 2016 guideline, opioid prescriptions dropped 44%. That sounds good. But it also led to over 20,000 additional overdose deaths from illicit drugs between 2017 and 2021, according to the DEA.

Why? Because many patients weren’t addicted. They were dependent. And when they were cut off without alternatives, they self-treated with dangerous street drugs. The real tragedy isn’t addiction. It’s misdiagnosis.

Today, 98% of insurance plans cover MAT for OUD. But only 67% have clear protocols for managing physical dependence in chronic pain patients. That gap is deadly.

What You Need to Know

- Physical dependence = your body adapts. It’s normal. It’s not addiction.

- Addiction = compulsive use despite harm. It’s a brain disorder.

- Withdrawal doesn’t prove addiction. Cravings, lying, stealing, job loss - those do.

- Stopping opioids suddenly because of withdrawal symptoms can be more dangerous than continuing them.

- If you’re on opioids for pain, ask your doctor: “Am I dependent? Or do I have OUD?”

- Dependence can be managed. Addiction can be treated.

There’s no shame in physical dependence. There’s no moral failing in needing pain relief. The real shame is when fear of stigma leads to undertreatment - and worse outcomes.

Can you be physically dependent on opioids without being addicted?

Yes - and most people who take opioids long-term are. Physical dependence is a biological adaptation. Addiction is a behavioral disorder. Nearly 100% of patients on daily opioids for over 30 days become dependent. Only about 8% develop Opioid Use Disorder. One doesn’t imply the other.

Does withdrawal mean I’m addicted?

No. Withdrawal is a sign of physical dependence, not addiction. If you stop opioids after long-term use, you’ll likely feel sick - nausea, sweating, anxiety, diarrhea. That’s your body adjusting. Addiction is when you keep using despite losing your job, relationships, or health. If you don’t crave the drug outside of medical need, and you don’t lie or steal to get it, you’re not addicted.

Can I stop opioids safely if I’m dependent?

Yes - but not suddenly. The CDC recommends tapering slowly: reduce your dose by 5-10% every 2-4 weeks. For higher doses (over 100 MME/day), go even slower - 5% per month. Medications like clonidine or lofexidine can help manage withdrawal symptoms. Always do this under medical supervision. Quitting cold turkey can cause severe complications.

What’s the difference between tolerance and addiction?

Tolerance means you need more of the drug to get the same effect - often because your body adapts. It’s common with long-term opioid use. Addiction is when you lose control - you keep using even when it harms your life. You might lie, steal, neglect responsibilities, or keep using despite overdose risk. Tolerance is biological. Addiction is behavioral.

Is buprenorphine just replacing one addiction with another?

No. Buprenorphine is part of Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT), which is evidence-based care for Opioid Use Disorder. It reduces cravings and withdrawal without causing euphoria. It lowers overdose risk by 70-80%. It allows people to work, care for families, and rebuild lives. It’s not a substitute - it’s a treatment. Like insulin for diabetes, it restores balance.

Annie Joyce

Physical dependence isn't a flaw-it's just your body doing its job. Opioids bind to receptors, your nervous system adapts, boom-you get withdrawal when you stop. That's biology, not weakness. I've seen patients taper off safely with clonidine and zero stigma. The real tragedy is when doctors panic and cut people off because they don't understand the difference between dependence and addiction.

Jack Havard

They're all just pushing a narrative. The CDC guidelines were never about patient care-they were about cutting costs and appeasing politicians. You think 8% OUD rate is real? That's sanitized data. The system wants you to believe dependence isn't dangerous so they can keep prescribing. Wake up.

Rachidi Toupé GAGNON

So true. Physical dependence = body adapts. Addiction = life falls apart. 🙌 If you're not stealing, lying, or losing your job over it-you're not addicted. Just be smart, taper slow, and talk to your doc. No shame.

Steve DESTIVELLE

Consider the nature of adaptation in biological systems when subjected to exogenous chemical modulation the human organism is not evolved to process with precision over prolonged durations this is not merely a pharmacological phenomenon it is an existential recalibration of homeostatic equilibrium the body does not distinguish between therapeutic intent and systemic disruption the distinction between dependence and addiction is a social construct designed to absolve institutions of responsibility

Neha Motiwala

Wait, wait, WAIT-so you're telling me the government, the AMA, the CDC, and Big Pharma are ALL lying to us? That this whole 'dependence isn't addiction' thing is just a cover-up so they can keep pumping out opioids? And doctors are just ignoring the signs? I knew it. I KNEW IT. My cousin went from pain meds to heroin because they didn't 'understand' the difference. This is a conspiracy. A. BIG. ONE.

Robert Petersen

This is such an important breakdown. I’ve had chronic pain for 12 years. I’ve been on opioids since I was 28. I’ve never used them to get high. I’ve never lied about it. I’ve never stolen. But when I tried to taper, my doctor acted like I was about to OD. I cried in his office. He didn’t get it. Thank you for saying this clearly. People need to hear it.

Craig Staszak

Dependence is normal. Addiction is a behavioral disorder. Period. The fact that we still confuse the two shows how much stigma is baked into medicine. We treat diabetes with insulin-we treat dependence with tapering. Why is one medical and the other moral? We need to fix the language before we fix the system.

Alyssa Williams

My mom was on 80 MME for 7 years. Tapered over 10 months. Withdrawal was hell-sweating, insomnia, nausea. But she didn’t crave it. Didn’t lie. Didn’t steal. Just wanted to feel normal again. They called her addicted. She cried for months. She wasn’t. She was just sick of being treated like a criminal.

Jason Pascoe

Thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’ve been in chronic pain since my accident. I’ve never used opioids to escape. I use them to sit with my kids. To work. To breathe. The idea that dependence = addiction is dangerous and outdated. We need better education-for patients and doctors.

Rob Turner

When I was in med school they taught us: dependence = biology. Addiction = behavior. Now? We’re told to fear opioids like they’re demon weed. The gap between science and practice is getting wider. I prescribe buprenorphine to patients with OUD. I taper others slowly. Both are valid. Both need compassion. Not judgment.

Vamsi Krishna

You think it's just about biology? Think deeper. The pharmaceutical industry engineered this. They knew dependence would follow. They knew doctors would panic. They knew patients would be cut off. And then? They sold heroin and fentanyl as the 'solution.' This isn't an accident. It's a business model. The 8% OUD rate? That's a lie. It's 30%. Maybe more. They just don't count the ones who died before they could be diagnosed.

christian jon

Oh please. You're telling me people on opioids for years aren't addicted? That's laughable. Look at the stats: 100,000+ overdose deaths last year. Most started with prescriptions. You think the system is that broken? No. People are weak. They get hooked. They lie. They steal. They destroy families. And now you want to excuse it with 'biological adaptation'? That's not medicine. That's moral surrender.

Autumn Frankart

So let me get this straight-doctors are just supposed to keep prescribing because someone might get withdrawal? What about the people who become addicted? What about the kids who find their parents’ pills? This isn’t about 'stigma'-it’s about responsibility. You can’t just say 'it’s biology' and wash your hands of the consequences. There’s a reason we regulate these drugs. Because they’re dangerous. Even if you’re 'just dependent.' You’re still one bad day away from disaster.

athmaja biju

India has 1.4 billion people. We don't have opioid crisis. We have discipline. We have resilience. We don't need pills to feel okay. This American obsession with painkillers is weakness disguised as medicine. You think dependence is normal? No. It's surrender. Stop blaming doctors. Stop blaming science. Start blaming the culture that turned pain into a commodity.