Safe Opioid Selection & Dosing for Kidney Failure

Opioid Dosing Calculator for Kidney Failure

Input Parameters

Results

When treating pain in patients with kidney failure, opioids renal failure are a class of analgesics that need special attention because the kidneys can’t clear them efficiently. The result is a tightrope walk between easing suffering and avoiding dangerous drug buildup. Below you’ll find the actual steps clinicians use to pick the right drug, adjust the dose, and keep patients safe.

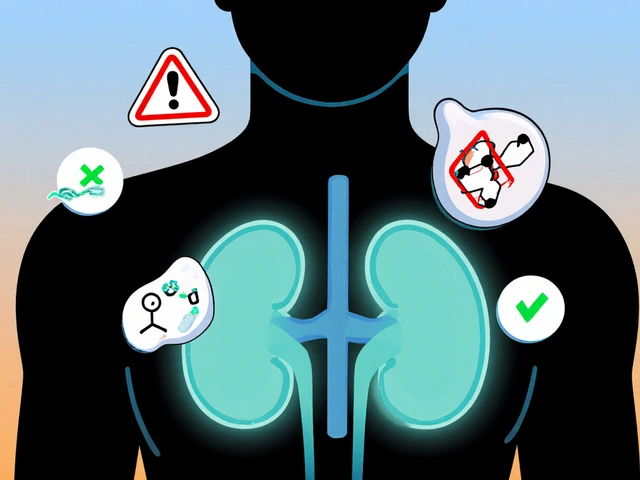

Why the Kidneys Matter for Opioids

Kidney function is measured by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). When GFR falls below 60 mL/min/1.73 m², drug clearance starts to slip. For opioids, the problem isn’t just the parent drug; many turn into active or toxic metabolites that the kidneys usually excrete. In advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end‑stage renal disease (ESRD), those metabolites can linger, causing neurotoxicity, respiratory depression, or severe constipation.

Studies from the American Academy of Family Physicians (2012) show that between 42 % and 85 % of dialysis patients report chronic pain, yet fewer than 15 % receive guideline‑concordant opioid therapy. The mismatch is largely due to uncertainty about which opioids stay safe when the kidneys are on the fritz.

Picking Safer Opioids: What the Guidelines Say

KDIGO’s 2013 position statement draws a clear line: avoid opioids that generate active renal metabolites. That means morphine, codeine, meperidine, and propoxyphene should never be used in moderate‑to‑severe CKD. Instead, the guidelines spotlight drugs that are cleared mostly by the liver or are highly lipophilic, such as:

- Fentanyl - 85 % hepatic metabolism, only ~7 % renal excretion.

- Buprenorphine - extensive hepatic metabolism, modest 30 % renal clearance.

- Hydromorphone - liver‑metabolized but its metabolite hydromorphone‑3‑glucuronide can accumulate in non‑dialyzed stage 5 CKD.

- Oxycodone - mixed clearance; use cautiously, keep daily dose ≤ 20 mg when CrCl < 30 mL/min.

- Methadone - safe from renal accumulation but needs ECG monitoring for QT prolongation.

Transdermal patches of fentanyl or buprenorphine are especially attractive because they bypass first‑pass metabolism and give steadier plasma levels. Just remember: never start a patch in an opioid‑naïve patient - the risk of overdose spikes dramatically.

Dosing Adjustments Based on GFR

The American Family Physician (2012) provides a practical percentage‑of‑usual‑dose chart. Below is a quick reference:

| GFR (mL/min/1.73 m²) | Morphine | Fentanyl | Methadone | Buprenorphine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 50 | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % |

| 10‑50 | 50‑75 % | 75‑100 % | 100 % | 100 % |

| < 10 | 25 % | 50 % | 50‑75 % | 100 % |

Note that buprenorphine does not require a dose cut‑back even in ESRD, but close monitoring for QT changes is still wise.

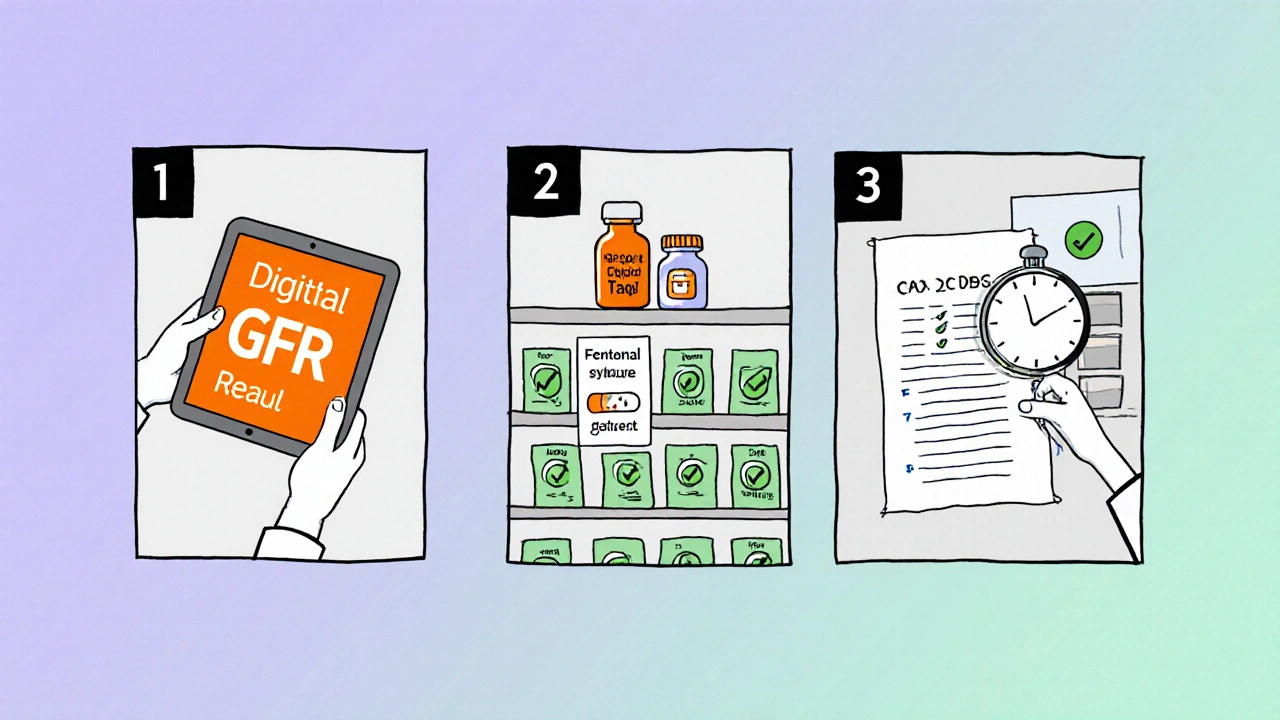

Step‑by‑Step Dosing Workflow

- Confirm the patient’s latest GFR or creatinine clearance (CrCl).

- Choose a opioid that the KDIGO list marks as safe (fentanyl, buprenorphine, low‑dose methadone, or oxycodone with limits).

- Start at 50 % of the usual adult dose if GFR < 15 mL/min, otherwise follow the percentage chart above.

- Extend the dosing interval by 50‑100 % when renal clearance drops below 30 mL/min.

- Re‑assess pain relief and side‑effects every 24‑48 hours before any upward titration.

- Document any dose adjustments and the rationale in the EMR decision‑support tool.

This routine keeps the patient comfortable while reducing the chance of drug accumulation.

Managing Opioid‑Related Side Effects in CKD

Opioid‑induced constipation hits 40‑80 % of CKD patients. The 2023 Cureus review points to naldemedine as the only peripherally‑acting mu‑opioid receptor antagonist (PAMORA) that doesn’t need dose changes in dialysis. A typical regimen is 0.2 mg once daily, taken with or without food.

Neurotoxicity from metabolites (e.g., morphine‑3‑glucuronide) can appear as myoclonus, delirium, or seizures. If any of these symptoms emerge, stop the offending drug, consider a short‑acting opioid like fentanyl for a brief bridge, and involve nephrology for dialysis‑based clearance if needed.

QT prolongation is a known risk with methadone and high‑dose buprenorphine. Obtain a baseline ECG, repeat after any dose increase above 30 mg methadone daily, and keep potassium > 4.0 mmol/L to minimize arrhythmia risk.

Special Populations: Dialysis and Transplant Recipients

During hemodialysis, fentanyl clearance is unpredictable, so most clinicians avoid its use on dialysis days. Buprenorphine, however, remains stable because only 30 % is renally cleared and the metabolite doesn’t accumulate dramatically.

For peritoneal dialysis patients, the same dosing rules apply, but watch for fluid shifts that could affect drug distribution.

Kidney transplant recipients often have improving GFR over time. Re‑evaluate opioid needs every month in the first three months post‑transplant, adjusting doses as the kidney function rebounds.

Putting It All Together: A Practical Checklist

- Identify pain type (nociceptive vs neuropathic) and severity.

- Check latest GFR/CrCl.

- Select a KDIGO‑approved opioid.

- Apply dose‑reduction chart; start low, go slow.

- Schedule reassessment at 24‑48 h intervals.

- Prescribe naldemedine for constipation; monitor ECG if using methadone or high‑dose buprenorphine.

- Document each step in the EMR, using built‑in renal‑dosing alerts.

Following this list keeps you on the safe side and demonstrates to regulators that you’re practicing evidence‑based medicine.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

The PAIN‑CKD cohort (NIDDK, 2021‑2026) is tracking outcomes of different opioid regimens in 1,200 CKD patients. Early data suggest that patients on lipophilic agents like fentanyl or buprenorphine have slower progression to ESRD than those on morphine‑based regimens.

Pharmacogenomics is another frontier. A 2023 Cureus review found that CYP2D6 poor metabolizers face a 3.2‑fold higher risk of morphine toxicity in CKD. While routine genotyping isn’t standard yet, it may become part of personalized pain plans within the next few years.

Finally, the 2024 KDIGO update is expected to incorporate newer opioids (tapentadol, newer PAMORAs) and real‑world data from integrated health‑system decision‑support tools, which have already cut inappropriate opioid prescriptions by nearly half in some networks.

Quick Reference Table

| Opioid | Renal Clearance | Metabolite Concern | Dose Adjust? | Preferred Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl | ~7 % | None clinically significant | Yes, reduce if GFR < 10 | Severe chronic pain, non‑dialysis CKD |

| Buprenorphine | ~30 % | Low‑risk metabolites | No reduction needed | Dialysis patients, stable chronic pain |

| Hydromorphone | ~30 % | Hydromorphone‑3‑glucuronide accumulates | Reduce 50 % if GFR < 30 | Short‑term breakthrough pain |

| Oxycodone | ~45 % | Active metabolites modestly cleared | Limit to 20 mg/day if CrCl < 30 | Mild‑moderate pain, not ESRD |

| Methadone | Negligible | No renal metabolites; QT risk | No renal reduction; ECG monitor | Patients needing long‑term opioid rotation |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use regular morphine for a patient on dialysis?

No. Morphine creates morphine‑3‑glucuronide, which builds up in dialysis patients and can cause severe neurotoxicity. Switch to fentanyl or buprenorphine instead.

Is a fentanyl patch safe for an opioid‑naïve kidney patient?

Never start a patch in an opioid‑naïve individual. The dose is too high initially and can cause respiratory depression. Begin with a low oral or buccal formulation, then consider a patch only after tolerance is established.

How often should I re‑check the GFR when a CKD patient is on opioids?

At least every three months, or sooner if the patient’s clinical status changes (e.g., infection, hospitalisation, change in dialysis schedule). Adjust the dose each time the GFR drops below a new threshold.

Do I need to give an extra dose of fentanyl after dialysis?

Generally no. Fentanyl’s renal clearance is low and dialysis does not reliably remove it. If a patient experiences breakthrough pain after a session, treat with a short‑acting opioid rather than increasing the baseline fentanyl dose.

What’s the best constipation treatment for CKD patients on opioids?

Naldemedine 0.2 mg daily is the only PAMORA shown to work without needing dose adjustment in both CKD and dialysis. Combine with stool softeners and adequate fluid intake when possible.

Joy Dua

In the nuanced arena of analgesic stewardship renal failure imposes a biochemical crucible wherein each opioid becomes a potential double‑edged sword; the clinician must wield pharmacokinetic insight as a scalpel dissecting risk from relief. The gradient of glomerular filtration rate dictates not just clearance but the very physiologic tapestry upon which metabolites accumulate, turning innocuous analgesia into neurotoxicity. A toxic analyst’s lens reveals that morphine and its glucuronide derivatives behave like stealthy saboteurs in the dialytic milieu, where even modest dosing can precipitate delirium. One must therefore prioritize agents whose hepatic biotransformation eclipses renal excretion, such as fentanyl, whose hepatic metabolism accounts for the lion’s share of its clearance. Buprenorphine, perched midway, offers a pharmacodynamic profile that tolerates the scarred nephron without surrendering potency. The clinician’s palette should be brushed with vivid caution, lest the colors of relief bleed into the greys of iatrogenic harm. In practice, a 50 % dose reduction for GFR below fifteen millilitres per minute is not a suggestion but a safeguard rooted in clinical evidence. Moreover, the art lies in continuous reassessment, a rhythmic pulse of evaluation every twenty‑four to forty‑eight hours, mirroring the kidney’s fickle ebb and flow. In essence, the renal‑failure context transforms opioid prescribing from a routine script into a dynamic choreography of dosage, monitoring, and interdisciplinary dialogue.

Tony Stolfa

Listen up crew opioid fans, the old school morphine talk is dead weight in dialysis wards-no more. If you gotta keep a patient on opioids you’re better off slinging fentanyl or buprenorphine and ditch the junk that piles up like trash in a busted kidney. Forget the romance of “just a little bit”; the data screams that even tiny doses of codeine turn toxic fast. So cut the crap, follow the KDIGO playbook, and watch the labs like hawks.

Charlene Gabriel

Hey everyone, let me take a moment to walk through why these guidelines feel like a lifeline for us caring for patients with chronic kidney disease. First, the reality is that pain doesn’t pause for lab values, and our patients deserve compassionate relief without the feared side‑effects. By selecting opioids that are primarily metabolized in the liver, such as fentanyl or buprenorphine, we respect the physiologic limits imposed by reduced GFR and avoid the accumulation of harmful metabolites that can cause myoclonus, delirium, or even seizures. Second, the dose‑reduction tables give us a concrete framework-starting at half the usual dose when GFR falls below 15 mL/min and adjusting upward only after careful reassessment helps keep us on the safe side. Third, the recommendation to re‑evaluate pain control and renal function every 24‑48 hours creates a feedback loop that catches changes early, especially in the context of intercurrent illnesses or hospitalizations that can further impair clearance. Fourth, addressing opioid‑induced constipation with naldemedine is a game‑changer, because constipation in CKD is already a big problem and adding a PAMORA that doesn’t need dose adjustments simplifies management. Fifth, keep an eye on the QT interval when using methadone or high‑dose buprenorphine; a baseline ECG and a follow‑up after dose changes protect against potentially fatal arrhythmias. Sixth, remember the special considerations for dialysis days-fentanyl isn’t reliably cleared, so we avoid dosing spikes and instead use short‑acting agents if breakthrough pain occurs. Seventh, for transplant recipients, the improving GFR over the first few months post‑surgery means we must steadily recalibrate the opioid regimen, reducing or stopping it as kidney function rebounds. Eighth, documentation in the EMR isn’t just bureaucracy-it creates an audit trail that demonstrates adherence to evidence‑based practice and shields us from regulatory scrutiny. Ninth, the emerging research into pharmacogenomics suggests that in the near future we may tailor opioid choices based on CYP2D6 status, further personalizing safety. Tenth, the ongoing PAIN‑CKD cohort hints that patients on lipophilic opioids may even experience slower progression to end‑stage disease, a hypothesis worth watching. Eleventh, all of these steps together form a practical checklist that can be taught to trainees, embedded in decision‑support tools, and shared across multidisciplinary teams. Twelfth, by embracing these strategies we not only alleviate suffering but also model high‑quality, patient‑centered care for the next generation of clinicians. Finally, let’s keep the conversation going, share our own experiences, and refine these practices as new evidence emerges.

Barna Buxbaum

Just a quick heads‑up: when you’re planning a fentanyl patch for a CKD patient, make sure the individual has already been titrated on a short‑acting formulation. That way you avoid the initial surge that can swamp a compromised kidney. Also, keep a log of GFR trends in the chart; seeing a steady drop over a few weeks is a cue to revisit the dosing chart. If you’re ever unsure, a brief consult with nephrology can clear up the most tangled questions about dialysis‑day dosing.

Miracle Zona Ikhlas

Safety first, always check the GFR before adjusting any opioid.

Carolyn Cameron

It is incumbent upon the practitioner to rigorously adhere to the KDIGO recommendations, thereby eschewing the perilous deployment of opioids with active renal metabolites. The scholarly consensus underscores the merit of hepatic‑centric clearance pathways, and any deviation from this principle warrants meticulous justification.

naoki doe

I’d add that the table you referenced could benefit from a column on dialysis‑specific adjustments, especially for agents with unpredictable clearance on haemodialysis days.

sarah basarya

Wow, what a dazzling display of medical textbook regurgitation-so thrilling to read yet utterly useless without real‑world nuance. It’s as if we’ve been handed a sterile recipe and told to bake a soufflé in a hurricane.

Samantha Taylor

Ah, the classic “let’s follow the guideline” mantra-because nothing screams competence like hiding behind a PDF while patients suffer in silence. One might suggest, in a stroke of originality, actually listening to the bedside concerns instead of reverently quoting tables.

Joe Langner

Guys, I think it’s cool to see all the data, but remember that every patient’s story is unique-sometimes a tiny tweak makes the huge diff, you know? Also, double‑check your typing; I saw a “GFR” once typed as “GFRR”.

Ben Dover

The analytical rigor applied to opioid selection in renal impairment is commendable, yet the exposition would benefit from a deeper dive into the pharmacodynamic variability observed across different patient subpopulations, thereby enriching the clinical applicability of the presented framework.

Katherine Brown

In the spirit of constructive discourse, I propose integrating a succinct algorithmic flowchart into the article, which would empower clinicians to rapidly navigate from GFR assessment to opioid selection, thereby enhancing both efficiency and safety.