Pterygium: How Sun Exposure Causes Growth and What Surgery Can Do

If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and noticed a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the white of your eye toward the pupil, you’re not alone. This is pterygium-often called "Surfer’s Eye"-and it’s not rare. It’s one of the most common eye surface conditions worldwide, especially in places where the sun beats down hard year-round. What starts as a harmless-looking bump can slowly creep onto the cornea, blur your vision, and make wearing contacts unbearable. The good news? You can stop it. And if it’s already growing, surgery can fix it-with much better results than in the past.

What Exactly Is a Pterygium?

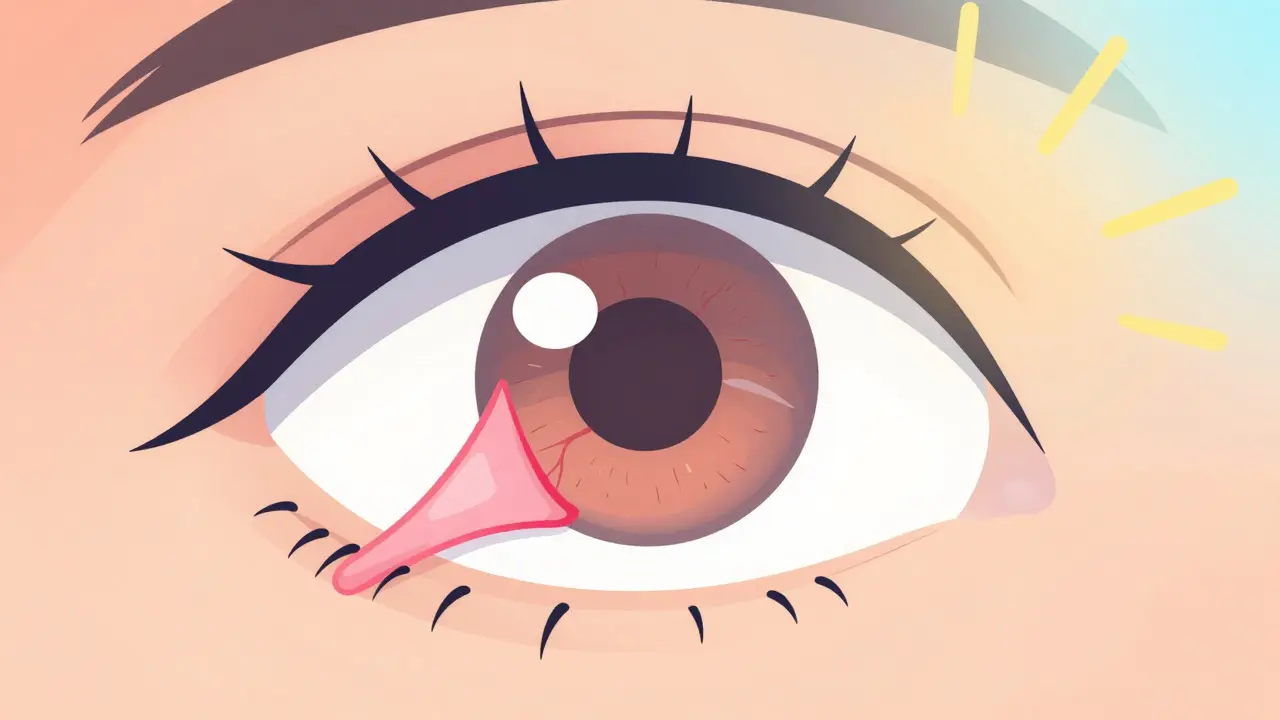

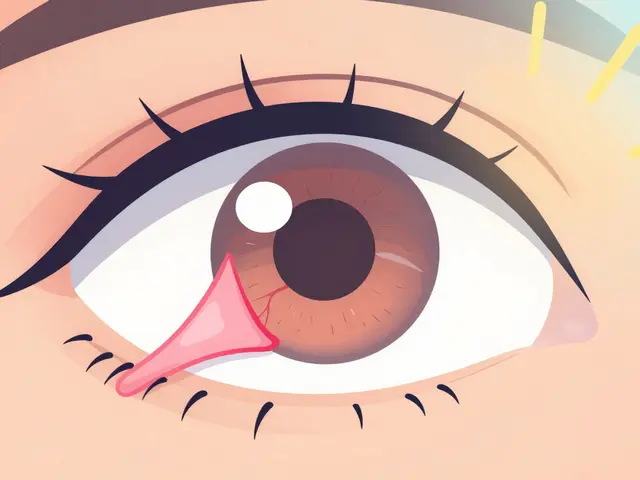

A pterygium is a noncancerous growth of the conjunctiva-the thin, clear tissue that covers the white part of your eye. It begins near the nose, usually, and stretches across the sclera (the white) toward the cornea (the clear front surface). When it reaches the cornea, it’s officially a pterygium. If it stays on the white part only, it’s called a pinguecula. The key difference? Pterygium crosses into the cornea. That’s what makes it a vision problem.

It looks like a triangular wing of tissue, often pink or red with visible tiny blood vessels. At first, it might be just a millimeter wide. But over time, under constant sun exposure, it can grow to 5 millimeters or more. About 60% of people with it have it in both eyes. It doesn’t hurt like an infection, but it irritates. You might feel grit, dryness, or redness-like sand is always in your eye.

Why Does the Sun Cause It?

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the main culprit. Not just a little sun. Not just beach days. It’s the cumulative exposure over years. Research shows people living within 30 degrees of the equator are 2.3 times more likely to develop pterygium than those farther north or south. In Australia, nearly 1 in 8 men over 60 have it. In tropical regions, outdoor workers see rates as high as 30%.

Studies confirm it: if your total UV exposure hits 15,000 joules per square meter over your lifetime, your risk jumps by 78%. That’s about 200 days a year in places like Brazil, India, or Australia where the UV index regularly hits 3 or higher. And UV doesn’t just come from direct sunlight-it reflects off water, sand, snow, and even concrete. So even if you’re not on a beach, you’re still getting hit.

It’s not just about being outside. Men are diagnosed more often than women-about 3 to 2. Why? Likely because more men work outdoors in construction, farming, fishing, or surfing. But anyone who spends hours outside without eye protection is at risk. And it’s not just older people. We’re seeing it in 30-year-olds who’ve spent years without sunglasses.

When Does It Become a Problem?

Many people live with small pterygia for years without symptoms. But when it grows over the cornea, things change. The cornea is supposed to be smooth and clear for sharp vision. When a pterygium invades it, the shape warps. That causes astigmatism-blurred or distorted vision. You might notice things look wavy, especially in bright light.

Other signs it’s becoming problematic:

- Difficulty wearing contact lenses because the growth makes the surface uneven

- Chronic redness or irritation that doesn’t go away with drops

- Feeling like something is always in your eye

- Visible growth that’s getting larger or darker

If you’re noticing any of these, it’s time for a slit-lamp exam. That’s the standard tool ophthalmologists use-it gives 10 to 40 times magnification to see exactly how far the growth has traveled. No blood tests or scans are needed. It’s all about what the doctor sees.

Surgery: When and How It Works

Most small pterygia don’t need surgery. Eye drops, artificial tears, and UV protection can slow or stop growth. But if it’s affecting your vision, causing constant discomfort, or just looks unsightly, surgery is the only way to remove it.

Here’s the reality: if you just scrape it off, it comes back. In the past, recurrence rates were 30% to 40%. That meant nearly half the people who had surgery ended up needing it again. Today, that’s changed.

Modern techniques use one of three main methods:

- Conjunctival autograft: The pterygium is removed, and a small piece of healthy conjunctiva is taken from another part of your eye (usually under the upper lid) and stitched over the area. This is the gold standard. Recurrence drops to about 8.7%.

- Mitomycin C: A chemical applied during surgery to kill off the cells that cause regrowth. Used alone or with a graft, it cuts recurrence to 5-10%.

- Amniotic membrane transplant: A newer option using tissue from donated placenta. It’s especially good for recurrent cases. Success rates are over 90% in recent studies.

The surgery itself takes about 30 to 40 minutes. It’s done under local anesthesia-you’re awake but feel no pain. Most people go home the same day. Recovery isn’t easy, though. Your eye will be red, swollen, and sensitive for 2 to 3 weeks. You’ll need steroid and antibiotic eye drops for 4 to 6 weeks. Some patients say the drop schedule is harder than the surgery.

What to Expect After Surgery

Most people report big improvements:

- 78% say recovery was quicker than expected

- 65% notice better vision within days

- 87% say irritation and redness improved dramatically

But it’s not perfect. About 32% of patients see regrowth within 18 months if they don’t follow post-op care. The biggest mistake? Stopping the drops too soon. Even if your eye looks fine, the cells underneath are still healing. Skipping drops raises your chance of recurrence.

Some people also worry about the cosmetic side. During healing, the eye can look very red or patchy. That fades. But it takes time. Patience is key.

How to Prevent It Before It Starts

Prevention is cheaper, easier, and painless. And it works.

The American Optometric Association and the Better Health Channel both agree: UV-blocking sunglasses and a wide-brimmed hat are your best defense. But not all sunglasses are equal. Look for ones labeled:

- Block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays

- Meet ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards

- Wrap around to block side exposure

Don’t rely on cheap drugstore shades. Many don’t block enough UV. And don’t wait until you’re older. Start young. Kids need protection too. UV damage adds up over decades.

Even on cloudy days, UV rays penetrate. Wear sunglasses when the UV index is 3 or higher-which happens over 200 days a year in tropical areas. If you surf, fish, farm, or bike outdoors, make this part of your daily routine, like brushing your teeth.

New Treatments on the Horizon

Science is moving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved a new preservative-free eye drop called OcuGel Plus, designed specifically for post-surgery healing. It reduced discomfort by 32% compared to regular artificial tears.

And there’s more. Phase II clinical trials are testing topical rapamycin-a drug that blocks the cells responsible for regrowth. Early results show a 67% drop in recurrence after 12 months. That’s huge.

By 2027, most eye surgeons expect to use laser-assisted removal more often. It’s faster, less invasive, and reduces tissue trauma. The future isn’t just about removing pterygium-it’s about stopping it before it comes back.

Who Needs to Be Most Careful?

You’re at highest risk if:

- You live near the equator (within 30 degrees north or south)

- You spend more than 4 hours a day outdoors

- You’re male and over 40

- You’ve had pterygium before

- You have a family history of it (some studies suggest genetics play a role)

But even if you don’t fit all those boxes, if you’re outside a lot, you’re not safe. One patient on Reddit said: "After 15 years of surfing without eye protection, I developed pterygium in both eyes. My vision got blurry when it reached the pupil." That’s not rare. It’s predictable.

What If You Can’t Afford Surgery?

Cost is a real barrier. In the U.S., surgery can run $2,000 to $5,000 per eye. In rural parts of developing countries, only 12% of people have access to surgical care. That’s a global health gap.

If you can’t get surgery right away, focus on slowing it down. Use UV-blocking sunglasses daily. Use lubricating eye drops to reduce irritation. See an eye doctor every 6 to 12 months to track growth. If it’s not touching your pupil, you might have years before you need surgery. But don’t wait until it’s too late.

Final Thought: Don’t Wait Until It Blurs Your Vision

Pterygium isn’t an emergency. But it’s not harmless either. Left unchecked, it can permanently change your vision. The good news? You have control. You can prevent it. You can stop it. And if it’s already there, modern surgery gives you a real chance to get your sight back-with low risk of recurrence.

Wear your sunglasses. Get checked. Don’t ignore that little pink wedge. Your eyes won’t thank you later if you do.

Can pterygium cause blindness?

No, pterygium doesn’t cause total blindness. But if it grows large enough to cover the pupil, it can cause significant blurry or distorted vision due to astigmatism. In rare cases, it can block light from entering the eye, leading to functional vision loss. Early treatment prevents this.

Is pterygium cancerous?

No, pterygium is not cancerous. It’s a benign growth. It doesn’t spread to other parts of the body or turn into melanoma or other eye cancers. However, because it can look similar to rare malignant tumors, doctors always confirm the diagnosis with a slit-lamp exam.

Can pterygium come back after surgery?

Yes, but not as often as before. Without modern techniques, recurrence rates were 30-40%. With conjunctival autografts and mitomycin C, that drops to 5-10%. Amniotic membrane transplants have success rates above 90% for recurrent cases. Following your doctor’s post-op care, especially using prescribed eye drops, is the biggest factor in preventing regrowth.

Are sunglasses enough to prevent pterygium?

Sunglasses are the most effective prevention tool-if they’re good ones. Look for labels that say they block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays and meet ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards. Wrap-around styles help block reflected UV from sand, water, and snow. Wearing a wide-brimmed hat adds another 50% protection. Consistency matters: wear them every day you’re outside, even when it’s cloudy.

How do I know if my pterygium is getting worse?

Watch for these signs: the growth is getting wider or longer, especially toward the pupil; your vision is becoming blurry or double; you can’t wear contact lenses anymore; or your eye feels more irritated, red, or dry than usual. If you notice any change, schedule an appointment with an ophthalmologist. A slit-lamp exam will show exactly how far it’s grown.

Can children get pterygium?

Yes, though it’s less common. Children who spend a lot of time outdoors without eye protection-especially in sunny, equatorial regions-are at risk. Early UV exposure builds up over time. It’s why experts recommend UV-blocking sunglasses for kids as young as 2. Prevention starts young.

What’s the difference between pterygium and pinguecula?

A pinguecula is a yellowish bump on the conjunctiva, usually near the nose, but it never grows onto the cornea. A pterygium starts as a pinguecula but extends onto the clear front of the eye (the cornea). That’s the key difference. Pinguecula is mostly a cosmetic issue. Pterygium can affect vision. About 70% of outdoor workers get pinguecula; only 30% develop pterygium.

Joy Nickles

Okay but like… why is everyone so chill about this?? I had one grow for 3 years and no one told me it could mess up my vision?? My optometrist just handed me drops and said "maybe wear sunglasses"?? Like?? I’m 28 and now I have astigmatism because I thought it was just dry eyes!!!

Bennett Ryynanen

Bro. I surfed for 12 years without sunglasses. Now I got pterygium in both eyes. Surgery was fine. The drops? Hell no. 6 weeks of that? I cried. But I’d do it again. Don’t be me. Wear the shades. 😤

Harriet Hollingsworth

It’s disgusting how many people ignore basic eye protection. This isn’t just a "cosmetic issue"-it’s preventable blindness. If you’re outside and not wearing UV-blocking sunglasses, you’re literally choosing to damage your eyes. And don’t even get me started on those cheap sunglasses from the gas station-they’re worse than nothing. You’re not protecting yourself, you’re fooling yourself.

Deepika D

Hey everyone, I’m a cataract surgeon in Bangalore and I see this every single day-especially in fishermen, farmers, and rickshaw drivers. The sad part? Most don’t even know what it’s called. They just say, "My eye is red and blurry." We do free camps in villages and give out cheap wraparound sunglasses-$2 each. It changes lives. If you’re reading this and you’re in a sunny country? Buy a pair for your uncle, your neighbor, your kid. One pair can stop a lifetime of pain. And yes, surgery works-but prevention is the real win. 🌞❤️

Darren Pearson

While the clinical data presented is largely accurate, I must express my concern regarding the casual tone employed throughout this article. The use of colloquialisms such as "Surfer’s Eye" and phrases like "don’t ignore that little pink wedge" undermines the medical gravity of the condition. A more formal, evidence-based presentation would better serve the public health imperative. Furthermore, the omission of peer-reviewed citations is a significant scholarly shortcoming.

Stewart Smith

So… you’re telling me I need to wear sunglasses like I wear deodorant? Huh. Guess I’ll start doing that. 🤡

Emma Hooper

Y’all act like this is some new horror movie plot. I’ve had a pinguecula since I was 19. It’s a bump. It doesn’t bite. I’ve seen people panic over this like it’s a tumor. Chill. Wear shades. Use drops. If it gets big, get it snipped. Done. Stop turning every eye thing into a trauma story.

Martin Viau

Interesting how this is framed as a "global health issue" when it’s essentially a tropical problem. In Canada, we don’t have this. We have frostbite and seasonal depression. Why are we even discussing this? Unless you’re in the equatorial belt, this is irrelevant. Also, "amniotic membrane transplant" sounds like a cult. Who approved this?

Chandreson Chandreas

Life’s weird, right? I used to think sunglasses were for rich people who didn’t want to squint. Then I spent a summer in Goa, surfing at dawn, and now I’ve got a tiny wing on my eye. 😅 But honestly? I’m not mad. It’s like a badge of honor for surviving the sun. Just got my first graft last month. Eye’s still red, but I’m alive. And yeah, I bought 3 pairs of proper shades. One for the car, one for the beach, one for my mom. 🌊🕶️

Aaron Bales

Key takeaway: UV exposure accumulates. It’s not about beach days-it’s about daily habits. If you’re outside for 15 minutes a day, 365 days a year, that’s 91 hours of UV. That’s enough. Sunglasses aren’t optional. They’re medical equipment. Period.

Retha Dungga

The eye is a mirror of the soul… and the sun steals pieces of it slowly… like time… like love… like forgotten promises… 🌞👁️🗨️

Jenny Salmingo

I grew up in Arizona. My dad made us wear hats and sunglasses every single day-even if we were just walking to the mailbox. I never got pterygium. My cousins in Texas? Two of them had surgery. It’s not luck. It’s habits. Teach your kids early. It’s that simple.

Robb Rice

Thanks for the detailed breakdown. I had surgery two years ago using the amniotic membrane technique. No recurrence. The drops were brutal, but worth it. One thing I’ll add: don’t skip the follow-ups. Even if it looks fine, the healing is happening under the surface. And yes-I wear my sunglasses now. Even indoors sometimes. Just in case. 😊